Los Angeles Times Why We Broke Up Review

| | |

The July 10, 2021 front folio | |

| Type | Daily paper |

|---|---|

| Format | Broadsheet |

| Possessor(due south) | Los Angeles Times Communications LLC (Nant Capital) |

| Founder(s) | Nathan Cole Jr. and Thomas Gardiner |

| President | Dr. Patrick Soon-Shiong |

| Editor | Kevin Merida |

| Founded | Dec 4, 1881 (1881-12-04) (as Los Angeles Daily Times) |

| Language | English |

| Headquarters | 2300 Eastward. Imperial Highway El Segundo, California 90245 |

| Country | United States |

| Circulation | 653,868 Daily (2013) 954,010 Sun (2013) 105,000 Digital (2018)[1] |

| ISSN | 0458-3035 (print) 2165-1736 (web) |

| OCLC number | 3638237 |

| Website | latimes |

| |

The Los Angeles Times (abbreviated as LA Times ) is a daily newspaper that started publishing in Los Angeles in 1881 and is now based in the adjacent suburb of El Segundo.[2] It has the fifth-largest circulation in the U.S. and is the largest American newspaper not headquartered on the East Coast.[3] The newspaper focuses its coverage of issues particularly salient to the West Declension, such as clearing trends and natural disasters. It has won more than forty Pulitzer Prizes for its coverage of these and other issues. As of June 18, 2018[update], buying of the paper is controlled by Patrick Soon-Shiong, and the executive editor is Norman Pearlstine.[4] It is considered a newspaper of tape in the U.Southward.[v] [half-dozen]

In the 19th century, the paper adult a reputation for borough boosterism and opposition to labor unions, the latter of which led to the bombing of its headquarters in 1910. The paper's contour grew substantially in the 1960s under publisher Otis Chandler, who adopted a more national focus. In recent decades the paper's readership has declined, and it has been aggress by a series of ownership changes, staff reductions, and other controversies. In January 2018, the paper's staff voted to unionize and finalized their first union contract on October xvi, 2019.[seven] The paper moved out of its historic downtown headquarters to a facility in El Segundo, California near Los Angeles International Airport in July 2018.

History [edit]

Otis era [edit]

The Times was first published on Dec 4, 1881, as the Los Angeles Daily Times nether the direction of Nathan Cole Jr. and Thomas Gardiner. It was kickoff printed at the Mirror printing institute, owned by Jesse Yarnell and T. J. Caystile. Unable to pay the printing bill, Cole and Gardiner turned the paper over to the Mirror Company. In the meantime, South. J. Mathes had joined the firm, and information technology was at his insistence that the Times continued publication. In July 1882, Harrison Gray Otis moved from Santa Barbara to become the paper's editor.[8] Otis made the Times a financial success.

Historian Kevin Starr wrote that Otis was a businessman "capable of manipulating the entire apparatus of politics and public stance for his own enrichment".[9] Otis'south editorial policy was based on borough boosterism, extolling the virtues of Los Angeles and promoting its growth. Toward those ends, the paper supported efforts to expand the urban center's water supply by acquiring the rights to the h2o supply of the distant Owens Valley.[10]

The efforts of the Times to fight local unions led to the bombing of its headquarters on Oct 1, 1910, killing twenty-ane people. Two matrimony leaders, James and Joseph McNamara, were charged. The American Federation of Labor hired noted trial attorney Clarence Darrow to represent the brothers, who eventually pleaded guilty.

Otis fastened a bronze eagle on top of a loftier frieze of the new Times headquarters building designed by Gordon Kaufmann, proclaiming anew the credo written by his wife, Eliza: "Stand Fast, Stand up Firm, Stand Certain, Stand True".[11] [12]

Chandler era [edit]

After Otis's expiry in 1917, his son-in-law, Harry Chandler, took control as publisher of the Times. Harry Chandler was succeeded in 1944 by his son, Norman Chandler, who ran the paper during the rapid growth of mail service-war Los Angeles. Norman's wife, Dorothy Buffum Chandler, became agile in civic diplomacy and led the attempt to build the Los Angeles Music Eye, whose principal concert hall was named the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in her honor. Family members are buried at the Hollywood Forever Cemetery near Paramount Studios. The site also includes a memorial to the Times Edifice bombing victims.

In 1935, the newspaper moved to a new, landmark Fine art Deco building, the Los Angeles Times Building, to which the paper would add other facilities until taking up the unabridged city block between Spring, Broadway, First and Second streets, which came to be known as Times Mirror Square and would house the paper until 2018. Harry Chandler, then the president and general director of Times-Mirror Co., declared the Los Angeles Times Building a "monument to the progress of our city and Southern California".[13]

The fourth generation of family unit publishers, Otis Chandler, held that position from 1960 to 1980. Otis Chandler sought legitimacy and recognition for his family's paper, often forgotten in the power centers of the Northeastern United States due to its geographic and cultural distance. He sought to remake the newspaper in the model of the nation's most respected newspapers, such every bit The New York Times and The Washington Post. Assertive that the newsroom was "the heartbeat of the business",[14] Otis Chandler increased the size and pay of the reporting staff and expanded its national and international reporting. In 1962, the paper joined with The Washington Postal service to course the Los Angeles Times–Washington Post News Service to syndicate articles from both papers for other news organizations. He also toned down the unyielding conservatism that had characterized the paper over the years, adopting a much more than centrist editorial stance.

During the 1960s, the paper won four Pulitzer Prizes, more than its previous nine decades combined.

Writing in 2013 about the pattern of newspaper ownership by founding families, Times reporter Michael Hiltzik said that:

The outset generations bought or founded their local paper for profits and as well social and political influence (which often brought more than profits). Their children enjoyed both profits and influence, but as the families grew larger, the subsequently generations found that only one or two branches got the ability, and everyone else got a share of the money. Eventually the coupon-clipping branches realized that they could make more than money investing in something other than newspapers. Under their pressure the companies went public, or split apart, or disappeared. That's the pattern followed over more than a century past the Los Angeles Times under the Chandler family.[fifteen]

The paper'southward early history and subsequent transformation was chronicled in an unauthorized history, Thinking Big (1977, ISBN 0-399-11766-0), and was 1 of four organizations profiled by David Halberstam in The Powers That Be (1979, ISBN 0-394-50381-3; 2000 reprint ISBN 0-252-06941-ii). Information technology has likewise been the whole or partial bailiwick of well-nigh thirty dissertations in communications or social science in the past four decades.[sixteen]

Erstwhile Times buildings [edit]

-

The 1886 Times edifice, northeast corner 1st/Broadway -

Times 1886 building afterwards bombing on October one, 1910 -

1912 Times building, demolished in 1938

-

Los Angeles Times Edifice, corner of 1st/Spring

-

The 1948 Crawford Improver (or Mirror Building), NW corner second/Leap, 2020 -

1973 Pereira Addition, SE corner 1st/Broadway

- 1881-1886, Temple and New High streets in the Los Angeles key business organisation district[17]

- 1886-1910, northeast corner First and Broadway, Los Angeles fundamental concern district, destroyed in a bombing in 1910[17]

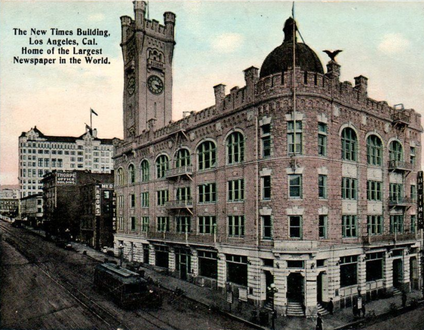

- 1912-1935, northeast corner First and Broadway, rebuilt as a four-story building with "castle-like" clock tower, opened 1912[17]

- 1935-2018, Times Mirror Square, the cake bounded by Start, Second, Leap streets and Broadway, Downtown Los Angeles

- 2018–present, El Segundo, California

Modern era [edit]

The Los Angeles Times was beset in the get-go decade of the 21st century by a change in buying, a bankruptcy, a rapid succession of editors, reductions in staff, decreases in paid circulation, the need to increment its Web presence, and a series of controversies.

The newspaper moved to a new headquarters building in El Segundo, near Los Angeles International Airport, in July 2018.[18] [19] [twenty] [21]

Ownership [edit]

In 2000, Times Mirror Visitor, publisher of the Los Angeles Times, was purchased past the Tribune Company of Chicago, Illinois, placing the paper in co-ownership with the then WB-affiliated (at present CW-affiliated) KTLA, which Tribune acquired in 1985.[22]

On April 2, 2007, the Tribune Company announced its acceptance of existent estate entrepreneur Sam Zell'due south offer to buy the Chicago Tribune, the Los Angeles Times, and all other company assets. Zell announced that he would sell the Chicago Cubs baseball order. He put upwardly for sale the company'south 25 pct involvement in Comcast SportsNet Chicago. Until shareholder approval was received, Los Angeles billionaires Ron Burkle and Eli Broad had the right to submit a higher bid, in which example Zell would have received a $25 million buyout fee.[23]

In Dec 2008, the Tribune Company filed for bankruptcy protection. The bankruptcy was a consequence of failing advertising acquirement and a debt load of $12.9 billion, much of it incurred when the newspaper was taken individual by Zell.[24]

On February seven, 2018, Tribune Publishing (formerly Tronc Inc.), agreed to sell the Los Angeles Times along with other southern California properties (The San Diego Spousal relationship-Tribune, Hoy) to billionaire biotech investor Patrick Presently-Shiong.[25] [26] This buy by Presently-Shiong through his Nant Capital investment fund was for $500 million, as well as the assumption of $ninety one thousand thousand in pension liabilities.[27] [28] The sale to Soon-Shiong closed on June 16, 2018.[four]

Editorial changes and staff reductions [edit]

In 2000, John Carroll, former editor of the Baltimore Sun, was brought in to restore the luster of the newspaper.[29] During his reign at the Times, he eliminated more than than 200 jobs, but despite an operating profit margin of 20 percent, the Tribune executives were unsatisfied with returns, and by 2005 Carroll had left the newspaper. His successor, Dean Baquet, refused to impose the additional cutbacks mandated by the Tribune Company.

Baquet was the commencement African-American to hold this type of editorial position at a top-tier daily. During Baquet and Carroll'south time at the newspaper, it won 13 Pulitzer Prizes, more than any other paper except The New York Times.[xxx] However, Baquet was removed from the editorship for non meeting the demands of the Tribune Grouping—as was publisher Jeffrey Johnson—and was replaced by James O'Shea of the Chicago Tribune. O'Shea himself left in January 2008 after a budget dispute with publisher David Hiller.

The paper's content and design style were overhauled several times in attempts to increase circulation. In 2000, a major modify reorganized the news sections (related news was put closer together) and changed the "Local" section to the "California" section with more all-encompassing coverage. Another major change in 2005 saw the Sunday "Opinion" section retitled the Lord's day "Electric current" section, with a radical change in its presentation and featured columnists. There were regular cross-promotions with Tribune-endemic boob tube station KTLA to bring evening-news viewers into the Times fold.

The paper reported on July 3, 2008, that it planned to cut 250 jobs by Labor Day and reduce the number of published pages by 15 percent.[31] [32] That included nigh 17 percentage of the news staff, as role of the newly private media company'southward mandate to reduce costs. "We've tried to get ahead of all the alter that'south occurring in the business and get to an organization and size that will be sustainable", Hiller said.[33] In Jan 2009, the Times eliminated the separate California/Metro department, folding it into the front section of the newspaper. The Times besides announced seventy job cuts in news and editorial or a 10 percent cutting in payroll.[34]

In September 2015, Austin Beutner, the publisher and chief executive, was replaced by Timothy East. Ryan.[35] On October 5, 2015, the Poynter Found reported that "'At least 50' editorial positions will be culled from the Los Angeles Times" through a buyout.[36] On this field of study, the Los Angeles Times reported with foresight: "For the 'funemployed,' unemployment is welcome."[37] Nancy Cleeland,[38] who took O'Shea's buyout offer, did then considering of "frustration with the newspaper's coverage of working people and organized labor"[39] (the trounce that earned her Pulitzer).[38] She speculated that the paper'due south revenue shortfall could be reversed by expanding coverage of economic justice topics, which she believed were increasingly relevant to Southern California; she cited the newspaper's attempted hiring of a "celebrity justice reporter" as an example of the wrong approach.[39]

On August 21, 2017, Ross Levinsohn, and then anile 54, was named publisher and CEO, replacing Davan Maharaj, who had been both publisher and editor.[40] On June xvi, 2018, the same twenty-four hours the sale to Patrick Before long-Shiong airtight, Norman Pearlstine was named executive editor.[iv]

On May 3, 2021, the newspaper announced that information technology had selected Kevin Merida to be the new executive editor. Merida is a senior vice president at ESPN and leads The Undefeated, a site focused on sports, race, and culture. Previously, he was the commencement Blackness managing editor at The Washington Mail service.[41]

Circulation [edit]

The Times has suffered connected reject in distribution. Reasons offered for the apportionment drop included a toll increase[42] and a rise in the proportion of readers preferring to read the online version instead of the print version.[43] Editor Jim O'Shea, in an internal memo announcing a May 2007, mostly voluntary, reduction in forcefulness, characterized the decrease in circulation as an "industry-wide problem" which the paper had to counter past "growing rapidly on-line", "break[ing] news on the Spider web and explicate[ing] and analyz[ing] it in our newspaper."[44]

The Times closed its San Fernando Valley press plant in early 2006, leaving press operations to the Olympic constitute and to Orangish County. Also that twelvemonth the paper appear its circulation had fallen to 851,532, down 5.4 per centum from 2005. The Times 's loss of apportionment was the largest of the meridian ten newspapers in the U.S.[45] Some observers believed that the drop was due to the retirement of circulation managing director Bert Tiffany. Yet, others thought the decline was a side event of a succession of short-lived editors who were appointed past publisher Marking Willes after publisher Otis Chandler relinquished solar day-to-day command in 1995.[14] Willes, the former president of General Mills, was criticized for his lack of agreement of the newspaper business, and was derisively referred to by reporters and editors every bit The Cereal Killer.[46]

Abased Los Angeles Times vending machine in Covina, California, in 2011

The Times 'south reported daily circulation in October 2010 was 600,449,[47] downward from a peak of 1,225,189 daily and one,514,096 Sunday in April 1990.[48] [49]

Internet presence and gratis weeklies [edit]

In December 2006, a team of Times reporters delivered direction with a critique of the newspaper's online news efforts known equally the Spring Street Project.[50] The report, which condemned the Times as a "spider web-stupid" organization",[50] was followed past a shakeup in management of the paper's website,[51] www.latimes.com, and a rebuke of impress staffers who had assertedly "treated change every bit a threat."[52]

On July 10, 2007, Times launched a local Metromix site targeting alive entertainment for immature adults.[53] A complimentary weekly tabloid print edition of Metromix Los Angeles followed in February 2008; the publication was the paper's first stand-lone impress weekly.[54] In 2009, the Times close downward Metromix and replaced it with Brand X, a blog site and gratis weekly tabloid targeting young, social networking readers.[55] Brand Ten launched in March 2009; the Brand X tabloid ceased publication in June 2011 and the website was shut down the following month.[56]

In May 2018, the Times blocked access to its online edition from most of Europe because of the European Matrimony'due south General Data Protection Regulation.[57] [58]

Other controversies [edit]

It was revealed in 1999 that a acquirement-sharing system was in place between the Times and Staples Middle in the preparation of a 168-folio magazine about the opening of the sports loonshit. The magazine'due south editors and writers were not informed of the agreement, which breached the Chinese wall that traditionally has separated advertizing from journalistic functions at American newspapers. Publisher Mark Willes besides had not prevented advertisers from pressuring reporters in other sections of the newspaper to write stories favorable to their bespeak of view.[59] Michael Kinsley was hired every bit the Opinion and Editorial (op-ed) Editor in April 2004 to help improve the quality of the opinion pieces. His role was controversial, for he forced writers to take a more decisive stance on issues. In 2005, he created a Wikitorial, the first Wiki by a major news organization. Although it failed, readers could combine forces to produce their ain editorial pieces. It was shut downward later being besieged with inappropriate textile. He resigned later that twelvemonth.[lx]

The Times drew fire for a concluding-infinitesimal story before the 2003 California recall ballot alleging that gubernatorial candidate Arnold Schwarzenegger groped scores of women during his movie career. Columnist Jill Stewart wrote on the American Reporter website that the Times did not do a story on allegations that former Governor Grey Davis had verbally and physically abused women in his role, and that the Schwarzenegger story relied on a number of anonymous sources. Further, she said, four of the six alleged victims were not named. She also said that in the case of the Davis allegations, the Times decided confronting printing the Davis story because of its reliance on anonymous sources.[61] [62] The American Guild of Newspaper Editors said that the Times lost more than than x,000 subscribers because of the negative publicity surrounding the Schwarzenegger article.[63]

On November 12, 2005, new op-ed Editor Andrés Martinez announced the dismissal of liberal op-ed columnist Robert Scheer and conservative editorial cartoonist Michael Ramirez.[64]

The Times also came under controversy for its decision to drib the weekday edition of the Garfield comic strip in 2005, in favor of a hipper comic strip Brevity, while retaining the Dominicus edition. Garfield was dropped altogether presently thereafter.[65]

Following the Republican Party'due south defeat in the 2006 mid-term elections, an Opinion piece by Joshua Muravchik, a leading neoconservative and a resident scholar at the bourgeois American Enterprise Institute, published on November xix, 2006, was titled 'Bomb Iran'. The article shocked some readers, with its hawkish comments in support of more unilateral activity by the Usa, this time against Iran.[66]

On March 22, 2007, editorial page editor Andrés Martinez resigned following an alleged scandal centering on his girlfriend'due south professional relationship with a Hollywood producer who had been asked to guest-edit a section in the newspaper.[67] In an open letter written upon leaving the paper, Martinez criticized the publication for allowing the Chinese Wall between the news and editorial departments to be weakened, accusing news staffers of lobbying the stance desk.[68]

In Nov 2017, Walt Disney Studios blacklisted the Times from attending press screenings of its films, in retaliation for September 2017 reportage by the paper on Disney's political influence in the Anaheim area. The company considered the coverage to be "biased and inaccurate". As a sign of condemnation and solidarity, a number of major publications and writers, including The New York Times, Boston Globe critic Ty Burr, Washington Post blogger Alyssa Rosenberg, and the websites The A.V. Club and Flavorwire, appear that they would cold-shoulder printing screenings of future Disney films. The National Society of Film Critics, Los Angeles Picture show Critics Association, New York Film Critics Circumvolve, and Boston Club of Picture show Critics jointly appear that Disney'southward films would be ineligible for their corresponding year-end awards unless the decision was reversed, condemning the decision equally being "antonymous to the principles of a free printing and [setting] a dangerous precedent in a fourth dimension of already heightened hostility towards journalists". On November 7, 2017, Disney reversed its determination, stating that the company "had productive discussions with the newly installed leadership at the Los Angeles Times regarding our specific concerns".[69] [70] [71]

Pulitzer Prizes [edit]

Through 2014 the Times had won 41 Pulitzer Prizes, including four in editorial cartooning, and i each in spot news reporting for the 1965 Watts Riots and the 1992 Los Angeles riots.[72]

- The Los Angeles Times received the 1984 Pulitzer Prize for Public Service for the paper series "Latinos".[73]

- Times sportswriter Jim Murray won a Pulitzer in 1990.

- Times investigative reporters Chuck Philips and Michael Hiltzik won the Pulitzer in 1999[74] for a year-long series that exposed corruption in the music business.[75]

- Times journalist David Willman won the 2001 Pulitzer Prize for Investigative Reporting; the organization cited "his pioneering expose of seven unsafe prescription drugs that had been approved by the Food and Drug Assistants, and an analysis of the policy reforms that had reduced the agency's effectiveness."[76] In 2004, the paper won five prizes, which is the third-almost past whatever paper in one year (behind The New York Times in 2002 (7) and The Washington Mail service in 2008 (6)).

- Times reporters Bettina Boxall and Julie Cart won a Pulitzer Prize for Explanatory Reporting in 2009 "for their fresh and painstaking exploration into the cost and effectiveness of attempts to combat the growing menace of wildfires across the western United States."[77]

- In 2011, Barbara Davidson was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Feature Photography "for her intimate story of innocent victims trapped in the metropolis's crossfire of deadly gang violence."[78]

- In 2016, the Times won the breaking news Pulitzer prize for its coverage of the mass shooting in San Bernardino, California.[79]

- In 2019, three Los Angeles Times reporters - Harriet Ryan, Matt Hamilton and Paul Pringle - won a Pulitzer Prize for their investigation into a gynecologist accused of abusing hundreds of students at the University of Southern California.[80]

Competition and rivalry [edit]

In the 19th century, the chief competition to the Times was the Los Angeles Herald, followed by the smaller Los Angeles Tribune. In Dec 1903, newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst began publishing the Los Angeles Examiner as a direct morning time competitor to the Times. [81] In the 20th century, the Los Angeles Express was an afternoon competitor, every bit was Manchester Boddy'southward Los Angeles Daily News, a Democratic newspaper.[82]

By the mid-1940s, the Times was the leading paper in terms of circulation in the Los Angeles metropolitan surface area. In 1948, information technology launched the Los Angeles Mirror, an afternoon tabloid, to compete with both the Daily News and the merged Herald-Express. In 1954, the Mirror absorbed the Daily News. The combined paper, the Mirror-News, ceased publication in 1962, when the Hearst afternoon Herald-Express and the forenoon Los Angeles Examiner merged to become the Herald-Examiner.[83] The Herald-Examiner published its last number in 1989. In 2014, the Los Angeles Register, published by Liberty Communications, then-parent visitor of the Orangish County Register was launched equally a daily newspaper to compete with the Times. By late September of the same year, the Los Angeles Register was folded.[84] [85]

Special editions [edit]

Midwinter and midsummer [edit]

Midwinter [edit]

For 69 years, from 1885[86] until 1954, the Times issued on New year's day'southward Twenty-four hour period a special annual Midwinter Number or Midwinter Edition that extolled the virtues of Southern California. At first, it was chosen the "Trade Number," and in 1886 it featured a special press run of "extra scope and proportions"; that is, "a twenty-4-page paper, and we hope to make it the finest exponent of this [Southern California] land that ever existed."[87] Ii years later, the edition had grown to "forty-eight handsome pages (9x15 inches), [which] stitched for convenience and better preservation," was "equivalent to a 150-page volume."[88] The last use of the phrase Trade Number was in 1895, when the edition had grown to xxx-six pages split among 3 separate sections.[89]

The Midwinter Number drew acclamations from other newspapers, including this one from The Kansas Urban center Star in 1923:

It is made up of five magazines with a total of 240 pages – the maximum size possible nether the postal regulations. It goes into every particular of information nearly Los Angeles and Southern California that the heart could desire. It is virtually a cyclopedia on the subject. It drips official statistics. In addition, it verifies the statistics with a profusion of illustration. . . . it is a remarkable combination of guidebook and travel magazine.[xc]

In 1948 the Midwinter Edition, every bit it was and so called, had grown to "seven big pic magazines in cute rotogravure reproduction."[91] The last mention of the Midwinter Edition was in a Times advertisement on January 10, 1954.[92]

Midsummer [edit]

Betwixt 1891 and 1895, the Times also issued a similar Midsummer Number, the outset one with the theme "The Land and Its Fruits".[93] Because of its issue date in September, the edition was in 1891 called the Midsummer Harvest Number.[94]

Zoned editions and subsidiaries [edit]

Front end page of the debut (March 25, 1903) issue of the brusk-lived The Wireless, published in Avalon.[95]

In 1903, the Pacific Wireless Telegraph Visitor established a radiotelegraph link between the California mainland and Santa Catalina Isle. In the summer of that year, the Times made utilise of this link to establish a local daily paper, based in Avalon, chosen The Wireless, which featured local news plus excerpts which had been transmitted via Morse code from the parent paper.[96] However, this effort plainly survived for just a piddling more than than ane twelvemonth.[97]

In the 1990s, the Times published various editions catering to far-flung areas. Editions included those from the San Fernando Valley, Ventura County, Inland Empire, Orangish County, San Diego County & a "National Edition" that was distributed to Washington, D.C., and the San Francisco Bay Surface area. The National Edition was closed in December 2004.

Some of these editions[ quantify ] were succeeded past Our Times, a group of customs supplements included in editions of the regular Los Angeles Metro paper.[ citation needed ]

A subsidiary, Times Community Newspapers, publishes the Daily Pilot of Newport Beach and Costa Mesa.[98] [99] From 2011 to 2013, the Times had published the Pasadena Sun.[100] It also had published the Glendale News-Press and Burbank Leader from 1993 to 2020, and the La Cañada Valley Lord's day from 2005 to 2020.[101]

On April thirty, 2020, Charlie Plowman, publisher of Outlook Newspapers, announced he would larn the Glendale News-Press, Burbank Leader and La Cañada Valley Sun from Times Community Newspapers. Plowman acquired the Due south Pasadena Review and San Marino Tribune in late Jan 2020 from the Salter family unit, who endemic and operated these two community weeklies.[ commendation needed ]

Features [edit]

One of the Times ' features was "Cavalcade One", a characteristic that appeared daily on the forepart page to the left-manus side. Established in September 1968, it was a identify for the weird and the interesting; in the How Far Can a Pianoforte Fly? (a compilation of Cavalcade One stories) introduction, Patt Morrison wrote that the column's purpose was to elicit a "Gee, that's interesting, I didn't know that" type of reaction.

The Times as well embarked on a number of investigative journalism pieces. A series in Dec 2004 on the Rex/Drew Medical Center in Los Angeles led to a Pulitzer Prize and a more thorough coverage of the hospital's troubled history. Lopez wrote a five-part serial on the borough and humanitarian disgrace of Los Angeles' Skid Row, which became the focus of a 2009 film, The Soloist. It also won 62 awards at the SND[ clarification needed ] awards.

From 1967 to 1972, the Times produced a Sun supplement called West magazine. W was recognized for its art design, which was directed by Mike Salisbury (who later became art director of Rolling Stone mag).[102] From 2000 to 2012, the Times published the Los Angeles Times Magazine, which started as a weekly and and so became a monthly supplement. The magazine focused on stories and photos of people, places, style, and other cultural diplomacy occurring in Los Angeles and its surrounding cities and communities. Since 2014, The California Lord's day Magazine has been included in the Sunday L.A. Times edition.

Promotion [edit]

Festival of Books [edit]

In 1996, the Times started the annual Los Angeles Times Festival of Books, in clan with the University of California, Los Angeles. It has panel discussions, exhibits, and stages during two days at the end of Apr each year.[103] In 2011, the Festival of Books was moved to the University of Southern California.[104]

Book prizes [edit]

Since 1980, the Times has awarded annual volume prizes. The categories are now biography, current involvement, fiction, get-go fiction, history, mystery/thriller, poesy, science and applied science, and immature adult fiction. In addition, the Robert Kirsch Award is presented annually to a living writer with a substantial connection to the American West whose contribution to American letters deserves special recognition".[105]

Los Angeles Times Grand Prix [edit]

From 1957 to 1987, the Times sponsored the Los Angeles Times 1000 Prix that was held over at the Riverside International Raceway in Moreno Valley, California.

Other media [edit]

Book publishing [edit]

The Times Mirror Corporation has also owned a number of book publishers over the years, including New American Library and C.V. Mosby, besides as Harry N. Abrams, Matthew Bender, and Jeppesen.[106]

In 1960, Times Mirror of Los Angeles bought the book publisher New American Library, known for publishing affordable paperback reprints of classics and other scholarly works.[107] The NAL connected to operate autonomously from New York and within the Mirror Company. In 1983, Odyssey Partners and Ira J. Hechler bought NAL from the Times Mirror Visitor for over $50 1000000.[106]

In 1967, Times Mirror caused C.Five. Mosby Visitor, a professional person publisher and merged information technology over the years with several other professional publishers including Resources Awarding, Inc., Yr Book Medical Publishers, Wolfe Publishing Ltd., PSG Publishing Company, B.C. Decker, Inc., among others. Somewhen in 1998 Mosby was sold to Harcourt Brace & Company to form the Elsevier Wellness Sciences group.[108]

Broadcasting activities [edit]

| | |

| Formerly | KTTV, Inc. (1947-1963) |

|---|---|

| Type | Private |

| Industry | Broadcast television Media |

| Founded | December 1947 (1947-12) |

| Defunct | 1993 |

| Fate | Caused by Argyle Television (sold to New Globe Communications in 1994) |

| Headquarters | Los Angeles, California United States |

| Area served | |

| Products | Broadcast and cable telly |

| Parent | The Times-Mirror Company (1947–1963, 1970–1993) Silent (1963–1970) |

The Times-Mirror Company was a founding owner of television station KTTV in Los Angeles, which opened in January 1949. It became that station's sole owner in 1951, after re-acquiring the minority shares information technology had sold to CBS in 1948. Times-Mirror besides purchased a former motion moving-picture show studio, Nassour Studios, in Hollywood in 1950, which was and so used to consolidate KTTV'south operations. Later to be known equally Metromedia Square, the studio was sold forth with KTTV to Metromedia in 1963.

After a vii-year hiatus from the medium, the business firm reactivated Times-Mirror Broadcasting Company with its 1970 purchase of the Dallas Times Herald and its radio and television stations, KRLD-AM-FM-TV in Dallas.[109] The Federal Communications Commission granted an exemption of its cross-buying policy and immune Times-Mirror to retain the newspaper and the television outlet, which was renamed KDFW-TV.

Times-Mirror Broadcasting later acquired KTBC-TV in Austin, Texas in 1973;[110] and in 1980 purchased a grouping of stations endemic past Newhouse Newspapers: WAPI-TV (now WVTM-TV) in Birmingham, Alabama; KTVI in St. Louis; WSYR-Tv set (now WSTM-Television set) in Syracuse, New York and its satellite station WSYE-TV (now WETM-Television receiver) in Elmira, New York; and WTPA-TV (now WHTM-TV) in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.[111] The visitor also entered the field of cablevision boob tube, servicing the Phoenix and San Diego areas, amidst others. They were originally titled Times-Mirror Cablevision, and were after renamed to Dimension Cablevision Television. Similarly, they besides attempted to enter the pay-Boob tube market, with the Spotlight movie network; it wasn't successful and was chop-chop shut downward. The cable systems were sold in the mid-1990s to Cox Communications.

Times-Mirror too pared its station group downward, selling off the Syracuse, Elmira and Harrisburg properties in 1986.[112] The remaining iv outlets were packaged to a new upstart property company, Argyle Television, in 1993.[113] These stations were acquired by New World Communications shortly thereafter and became cardinal components in a sweeping shift of network-station affiliations which occurred between 1994 and 1995.

Stations [edit]

| City of license / market | Station | Channel Idiot box / (RF) | Years owned | Current buying status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birmingham | WVTM-TV | 13 (xiii) | 1980–1993 | NBC affiliate endemic past Hearst Television |

| Los Angeles | KTTV one | 11 (11) | 1949–1963 | Play a trick on owned-and-operated (O&O) |

| St. Louis | KTVI | two (43) | 1980–1993 | Fox affiliate owned by Nexstar Media Group |

| Elmira, New York | WETM-Goggle box | 18 (18) | 1980–1986 | NBC affiliate endemic by Nexstar Media Grouping |

| Syracuse, New York | WSTM-TV | 3 (24) | 1980–1986 | NBC affiliate endemic by Sinclair Broadcast Group |

| Harrisburg - Lancaster - Lebanon - York | WHTM-TV | 27 (ten) | 1980–1986 | ABC affiliate endemic by Nexstar Media Group |

| Austin, Texas | KTBC-TV | 7 (7) | 1973–1993 | Play a trick on owned-and-operated (O&O) |

| Dallas - Fort Worth | KDFW-Telly ii | 4 (35) | 1970–1993 | Fox endemic-and-operated (O&O) |

Notes:

- 1 Co-owned with CBS until 1951 in a joint venture (51% owned by Times-Mirror, 49% endemic by CBS);

- 2 Purchased along with KRLD-AM-FM equally part of Times-Mirror's acquisition of the Dallas Times Herald. Times-Mirror sold the radio stations to comply with FCC cross-buying restrictions.

Employees [edit]

Unionization [edit]

On January 19, 2018, employees of the news department voted 248–44 in a National Labor Relations Board election to exist represented by the NewsGuild-CWA.[114] The vote came despite aggressive opposition from the paper's management squad, reversing more than a century of anti-union sentiment at ane of the biggest newspapers in the country.

Writers and editors [edit]

- Dean Baquet, editor 2000–2007

- Martin Baron, assistant managing editor 1979–1996

- James Bassett, reporter, editor 1934–1971

- Skip Bayless, sportswriter 1976–1978

- Barry Bearak, reporter 1982–1997

- Jim Bellows (1922–2005), editor 1967–1974

- Sheila Benson, flick critic 1981–1991

- Martin Bernheimer, music critic, 1982 Pulitzer Prize for Criticism

- Bettina Boxall, reporter, 2009 Pulitzer Prize

- Jeff Brazil, reporter 1993–2000

- Harry Carr (1877–1936), reporter, columnist, editor

- John Carroll, editor 2000–2005

- Julie Cart, reporter, 2009 Pulitzer Prize

- Charles Champlin (1926–2014), pic critic 1965–1980

- Sewell Chan, editor of the editorial page

- Michael Cieply, amusement writer

- Shelby Coffey 3, editor 1989–1997

- K.C. Cole, science writer

- Michael Connelly, crime reporter, novelist

- Borzou Daragahi, Beirut bureau chief

- Manohla Dargis, picture critic

- Meghan Daum, columnist

- Anthony 24-hour interval (1933–2007), op-ed author, editor 1969–89

- Frank del Olmo (1948–2004), reporter, editor 1970–2004

- Al Delugach (1925–2015), reporter 1970–1989

- Barbara Demick, Beijing bureau main, writer

- Robert J. Donovan (1912–2003), Washington bureau chief

- Mike Downey, columnist 1985–2001

- Bob Drogin, national political reporter

- Roscoe Drummond (1902–1983), syndicated columnist

- Due east.V. Durling (1893–1957), columnist 1936–1939

- Bill Dwyre, sports editor and columnist 1981–2015

- Braven Dyer, sports reporter, sports editor 1925-1965

- Louis Dyer, reporter, editor LA Mirror, Home Mag 1934-1955

- William J. Eaton (1930–2005), contributor 1984–1994

- Richard Eder (1932–2014), volume critic, 1987 Pulitzer Prize for Criticism

- Gordon Edes, sportswriter 1980–1989

- Helene Elliott, sports columnist

- Leonard Feather (1914–1994), jazz critic

- Dexter Filkins, strange correspondent 1996–1999

- Nikki Finke, entertainment reporter

- Thomas Francis Ford (1873–1958), U.South. Congress member, literary and rotogravure editor, City Council fellow member

- Douglas Frantz, managing editor 2005–2007

- Jeffrey Gettleman, Atlanta bureau chief 1999–2002

- Jonathan Gold, nutrient writer, 2007 Pulitzer Prize

- Patrick Goldstein, film columnist 2000–2012

- Carl Greenberg (1908–1984), political writer

- Jean Guerrero, opinion columnist

- Joyce Haber, gossip columnist 1966–1975

- Nib Henry (1890–1970), columnist 1939–1970

- Robert Hilburn, music writer 1970–2005

- Shani Olisa Hilton, Deputy Managing editor

- Michael Hiltzik, investigative reporter, 1999 Pulitzer Prize for Beat Reporting

- Hedda Hopper (1885–1966), Hollywood columnist 1938–1966

- L. D. Hotchkiss (1893–1964), editor 1922–1958

- Pete Johnson, stone critic of the 1960s

- David Cay Johnston, reporter 1976–1988

- Jonathan Kaiman, Asia contributor 2015-2016

- K. Connie Kang (1942–2019) commencement female person Korean American announcer

- Philip P. Kerby, 1976 Pulitzer Prize for Criticism

- Ann Killion, sportswriter 1987–1988

- Grace Kingsley (1874–1962), film columnist 1914–1933

- Michael Kinsley, op-ed page editor 2004–2005

- Christopher Knight, art critic, 2020 Pulitzer Prize for Criticism

- William Knoedelseder, business concern writer

- Howard Lachtman, literary critic[115] [116]

- David Lamb (1940–2016), correspondent 1970–2004

- David Laventhol (1933–2015), publisher 1989–1994

- David Lazarus, business organization columnist

- Rick Loomis, photojournalist, 2007 Pulitzer Prize for Explanatory Reporting

- Stuart Loory (1937–2015), White Business firm correspondent 1967–1971

- Steve Lopez, columnist

- Charles Fletcher Lummis (1859–1928), city editor 1884–1888

- Al Martinez (1929–2015), columnist 1984–2009

- Andres Martinez, op-ed page editor 2004–2007

- Dennis McDougal, reporter 1982–1992

- Usha Lee McFarling, reporter, 2007 Pulitzer Prize for Explanatory Reporting

- Kristine McKenna, music journalist 1977–1998

- Mary McNamara, Telly critic, 2015 Pulitzer Prize for Criticism

- Doyle McManus, Washington agency principal

- Charles McNulty, theater critic

- Alan Miller, 2003 Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting

- T. Christian Miller, investigative journalist 1999–2008

- Kay Mills, editorial writer 1978–1991

- Carolina Miranda, arts and culture critic 2014–present

- J.R. Moehringer, feature writing, 2000 Pulitzer Prize for Feature Writing

- Patt Morrison, columnist

- Suzanne Muchnic, art critic 1978–2009

- Kim Murphy, assistant managing editor for foreign and national news, 2005 Pulitzer Prize

- Jim Murray (1919–1998), sports columnist, 1990 Pulitzer Prize for Commentary

- Sonia Nazario, characteristic writing, 2003 Pulitzer Prize

- Dan Neil, columnist, 2004 Pulitzer Prize for Criticism

- Chuck Neubauer, investigative journalist

- Ross Newhan, baseball author 1967–2004

- Jack Nelson (1929–2009), political reporter, 1960 Pulitzer Prize for Local Reporting[117]

- Anne-Marie O'Connor, reporter

- Nicolai Ouroussoff, architectural critic

- Scot J. Paltrow, financial journalist 1988–1997

- Olive Percival, columnist

- Beak Plaschke, sports columnist

- Michael Parks, strange correspondent, editor, 1987 Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting

- Russ Parsons, nutrient author

- Mike Penner (1957–2009) (Christine Daniels), sportswriter

- Chuck Philips, investigative reporter, 1999 Pulitzer Prize for Trounce Reporting

- Michael Phillips, film critic

- George Ramos (1947–2011), reporter 1978–2003

- Richard Read, reporter, 1999 Pulitzer Prize 2001 Pulitzer Prize

- Ruth Reichl, eating house and food writer 1984–1993

- Rick Reilly, sportswriter 1983–1985

- James Risen, investigative journalist 1984–1998

- Howard Rosenberg, TV critic, 1985 Pulitzer Prize for Criticism

- Tim Rutten, columnist 1971–2011

- Harriet Ryan, Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative reporter

- Ruth Ryon (1944–2014), real manor writer 1977–2008

- Morrie Ryskind, feature author 1960–1971

- Kevin Sack, Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting in 2003

- Ruben Salazar (1928–1970), reporter, correspondent 1959–70

- Robert Scheer, national contributor 1976–1993

- Lee Shippey (1884–1969), columnist 1927–1949

- David Shaw (1943–2005), 1991 Pulitzer Prize for Criticism

- Gaylord Shaw, reporter, 1978 Pulitzer Prize

- Gene Sherman (1915–1969), reporter, 1960 Pulitzer Prize

- Barry Siegel, feature writing, 2002 Pulitzer Prize

- T. J. Simers, sports columnist 1990–2013

- Jack Smith (1916–1996), columnist 1953–1996

- Bob Sipchen, editorial writing, 2002 Pulitzer Prize

- Frank Sotomayor, reporter, editor

- Bill Stall (1937–2008), editorial writing, 2004 Pulitzer Prize

- Joel Stein, columnist

- Jill Stewart, reporter 1984–1991

- Rone Tempest, investigative reporter 1976–2007

- Kevin Thomas, film critic 1962–2005

- William F. Thomas (1924–2014), editor 1971–1989

- Hector Tobar, columnist, book critic

- William Tuohy (1926–2009), foreign correspondent, 1969 Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting

- Kenneth Turan, motion picture critic

- Julia Turner, deputy managing editor

- Peter Wallsten, national political reporter

- Matt Weinstock (1903–1970), columnist

- Kenneth R. Weiss, 2007 Pulitzer Prize for Explanatory Reporting

- Nick Williams (1906–1992), editor 1958–1971

- David Willman, 2001 Pulitzer Prize for Investigative Reporting

- Michael Wines, correspondent 1984–1988

- Jules Witcover, Washington contributor 1970–1972

- Cistron Wojciechowski, sportswriter 1986–1996

- Willard Huntington Wright (1888–1939), literary editor

- Kimi Yoshino, managing editor

Cartoonists [edit]

- Paul Francis Conrad (1924–2010), Pulitzer Prize in 1964, 1971, and 1984

- Ted Rall

- David Horsey, Pulitzer Prize in 1999 and 2003

- Frank Interlandi (1924–2010)

- Michael Patrick Ramirez, Pulitzer Prize in 1994 and 2008

- Bruce Russell, Pulitzer Prize in 1946

Photographers [edit]

- Don Bartletti, Pulitzer Prize in 2003

- Carolyn Cole, Pulitzer Prize in 2004

- Rick Corrales (1957–2005), photographer 1981–1995

- Mary Nogueras Frampton, one of the paper's outset female photographers

- Jose Galvez, photographer 1980–1992

- John 50. Gaunt, Jr., Pulitzer Prize in 1955

- Rick Loomis, photojournalist, 2007 Pulitzer Prize

- Anacleto Rapping, multiple Pulitzer Prizes

- George Rose, photojournalist 1977–1983

- George Strock, photojournalist of the 1930s

- Annie Wells, photojournalist 1997–2008

- Clarence Williams, Pulitzer Prize in 1998

Encounter as well [edit]

- Victorian Downtown Los Angeles

References [edit]

- ^ "Total Circ for US Newspapers". Archived from the original on June 11, 2013. Retrieved Oct 21, 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Los Angeles Times | History, Ownership, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica . Retrieved October 1, 2020.

- ^ "The 10 Most Popular Daily Newspapers In The United States". August 2017. Retrieved Oct 24, 2017.

- ^ a b c Arango, Tim (June eighteen, 2018). "Norman Pearlstine Named Editor of The Los Angeles Times". The New York Times . Retrieved June 18, 2018.

- ^ Corey Frost; Karen Weingarten; Doug Babington; Don LePan; Maureen Okun (May 30, 2017). The Broadview Guide to Writing: A Handbook for Students (6th ed.). Broadview Printing. pp. 27–. ISBN978-i-55481-313-1 . Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ^ Caulfield, Mike (January eight, 2017), "National Newspapers of Record", Web Literacy for Student Fact-Checkers, Self-published, retrieved July xx, 2020

- ^ "Los Angeles Times reaches historic agreement with its newsroom union". Los Angeles Times. October 17, 2019. Retrieved November 15, 2019.

- ^ "Mirror Acorn, 'Times' Oak," Los Angeles Times, October 23, 1923, page Ii-ane Access to this link requires the use of a library card.

- ^ Starr, Kevin (1985). Inventing the Dream: California Through the Progressive Era . New York: Oxford University Press. p. 228. ISBN0-xix-503489-ix. OCLC 11089240.

- ^ Arango, Tim; Nagourney, Adam (January 30, 2018). "A Paper Tears Apart in a City That Never Quite Came Together". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- ^ Berges, Marshall. The Life and Times of Los Angeles: A Paper, A Family and A City. New York: Atheneum. p. 25.

- ^ Clarence Darrow: Biography and Much More from Answers.com at www.answers.com

- ^ DiMassa, Cara Mia (June 26, 2008). "Much has changed around the Los Angeles Times Building". Los Angeles Times . Retrieved June 26, 2008.

- ^ a b McDougal, Dennis (2002). Privileged Son: Otis Chandler and the Rise and Autumn of the 50.A. Times Dynasty. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo. ISBN0-306-81161-8. OCLC 49594139.

- ^ Hiltzik, Michael (August 6, 2013). "Washington Post Purchase: Tin Jeff Bezos Gear up Newspapers' Business Model?". Los Angeles Times . Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ^ ProQuest Dissertation Abstracts. Retrieved June eight, 2007.

- ^ a b c Los Angeles Times Building, Water and Power Assembly

- ^ Chang, Andrea (Apr 17, 2018). "50.A. Times volition move to 2300 East. Imperial Highway in El Segundo". Los Angeles Times . Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- ^ "Biotech billionaire takes control of the LA Times, names new executive editor". Orangish County Register. Associated Press. June 18, 2018. Retrieved July nineteen, 2018.

- ^ Curwen, Thomas (July twenty, 2018). "For a brief, shining moment, Times Mirror Foursquare was Fifty.A.'s Camelot". Los Angeles Times . Retrieved July 21, 2018.

- ^ Miranda, Carolina (July 17, 2018). "Ugly carpets and green marble: The design of the Los Angeles Times buildings changed along with the city, though not ever gracefully". Los Angeles Times . Retrieved July 21, 2018.

- ^ "Tribune called on to sell L.A. Times". CNN. September 18, 2006. Retrieved June nineteen, 2012.

- ^ "Tribune goes to Zell". Chicago Sun-Times. April three, 2007. Archived from the original on September 18, 2008.

- ^ James Rainey & Michael A. Hiltzik (Dec ix, 2008). "Owner of L.A. Times files for bankruptcy". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Koren, Meg James, James Rufus (Feb 7, 2018). "Billionaire Patrick Soon-Shiong reaches deal to buy L.A. Times and San Diego Union-Tribune". Los Angeles Times . Retrieved Feb eight, 2018.

- ^ "Tronc in Talks to Sell Flagship Los Angeles Times to Billionaire Investor". February half-dozen, 2018. Retrieved Feb six, 2018.

- ^ "Tronc Pushes Into Digital Future After Los Angeles Times Sale". February vii, 2018. Retrieved February 7, 2018.

- ^ James, Meg; Chang, Andrea (Apr thirteen, 2018). "Patrick Soon-Shiong plans to motion Los Angeles Times to new campus in El Segundo". Los Angeles Times . Retrieved April xiii, 2018.

- ^ "John Carroll, former Baltimore Dominicus and Los Angeles Times editor, dies at 73". TheGuardian.com. June fourteen, 2015.

- ^ Pappu, Sridhar (March–April 2007). "Reckless Disregard: Dean Baquet on the gutting of the Los Angeles Times". Mother Jones.

- ^ Hiltzik, Michael A. (July 3, 2008). "Los Angeles Times to cut 250 jobs, including 150 from news staff: The paper cites falling ad acquirement in economic slowdown". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Politi, Daniel (July three, 2008). "Today's Papers: "You Take Been Liberated"". Slate.

- ^ Shiva Ovide (July iii, 2008). "Los Angeles Times to Cut Staff". The New York Times . Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- ^ Roderick, Kevin (January 30, 2009). "Los Angeles Times kills local news department". LA Observed. Retrieved August 8, 2016.

- ^ Somaiya, Ravi (September 8, 2015). "Austin Beutner Ousted as Los Angeles Times Publisher". The New York Times.

- ^ Mullin, Benjamin (October 5, 2015). "Tribune Publishing CEO announces buyouts". Poynter. Archived from the original on Dec 8, 2015. Retrieved Baronial viii, 2016.

- ^ "For the 'funemployed,' unemployment is welcome". LA Times. June 4, 2009. Retrieved August eight, 2016.

- ^ a b Due east&P Staff (May 28, 2007). "Pulitzer Winner Explains Why She Took 'Fifty.A. Times' Buyout". Editor & Publisher. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. Retrieved May 28, 2007.

- ^ a b Cleeland, Nancy (May 28, 2007). "Why I'm Leaving The L.A. Times". Huffington Mail.

- ^ James, Million (August 21, 2017). "Ross Levinsohn is named the new publisher and CEO of the 50.A. Times equally top editors are ousted". Retrieved August 21, 2017.

- ^ Robertson, Katie (May 3, 2021). "Los Angeles Times Hires Its Side by side Superlative Editor: Kevin Merida, of ESPN". The New York Times . Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ Shah, Diane, "The New Los Angeles Times" Columbia Journalism Review 2002, 3.

- ^ Rainey, James, "Newspaper Circulation Continues to Fall," Los Angeles Times May i, 2007: D1.

- ^ E&P Staff (May 25, 2007). "California Dissever: 57 More Task Cuts at 'L.A. Times'". Editor & Publisher. Nielsen Business organisation Media, Inc. Retrieved May 28, 2007.

- ^ Lieberman, David (May 9, 2006). "Newspaper sales dip, but websites gain". USA Today.

- ^ Shaw, David. "Crossing the Line". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on Oct 24, 2015. Retrieved Oct 3, 2016.

- ^ Bill Cromwell (April 26, 2010). "Like Newspaper Revenue, the Decline in Circ Shows Signs of Slowing". editorandpublisher.com. Archived from the original on Oct 27, 2010. Retrieved Apr 26, 2010.

- ^ "The Los Angeles Times' history". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved May 15, 2017.

- ^ Equally told to RJ Smith. "Ripped from the headlines - Los Angeles Magazine". Lamag.com. Retrieved Jan 12, 2009.

- ^ a b Saar, Mayrav (January 26, 2007). "LAT's Scathing Internal Memo. Read It Here". FishbowlLA. mediabistro.com. Archived from the original on October 30, 2007.

- ^ Roderick, Kevin (January 24, 2007). "Times retools on spider web — again". LA Observed.

- ^ Welch, Matt (January 24, 2007). "Spring Street Project unveiled!". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Metromix Makes Cool Debut". Los Angeles Times. July 10, 2007. Retrieved October 3, 2013.

- ^ Ives, Nate (February thirteen, 2008). "Los Angeles Times Launches Free Weekly". Advertising Age. Retrieved Oct 3, 2013.

- ^ "Editor announces weekly tabloid aimed at social-networking readers". Los Angeles Times. March 25, 2009. Retrieved October iii, 2013.

- ^ Roderick, Kevin (June 29, 2011). "L.A. Times folds Brand X". LA Observed. Retrieved October three, 2013.

- ^ Petroff, Alanna. "LA Times takes down website in Europe as privacy rules bite". CNN.

- ^ Newcomb, Alyssa (May 25, 2018). "Chicago Tribune, Los Angeles Times block European users due to GDPR". CBS News. NBC Universal. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ Elderberry, Sean (November 5, 1999). "Meltdown at the L.A. Times". Salon.com . Retrieved March 26, 2007.

- ^ Naughton, Philippe (June 21, 2005). "Foul language forces LA Times to pull plug on 'wikitorial'". The Times . Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ Stewart, Jill (October 14, 2003). "How the Los Angeles Times Really Decided to Publish its Accounts of Women Who Said They Were Groped". jillstewart.net. Archived from the original on February 1, 2008.

- ^ Cohn, Gary; Hall, Carla; Welkos, Robert W. (October 2, 2003). "Women Say Schwarzenegger Groped, Humiliated Them". Los Angeles Times. [ dead link ] Alt URL

- ^ "ASNE recognizes Los Angeles Times editor for leadership". ASNE.org. American Society of Newspaper Editors. March 24, 2004. Archived from the original on November 15, 2007.

- ^ "LA Times Fires Longtime Progressive Columnist Robert Scheer". Commonwealth Now! . Retrieved October 15, 2018.

- ^ Astor, Dave (January 5, 2005). "'L.A. Times' Drops Daily 'Garfield' equally the Comic Is Blasted and Praised". Editor & Publisher. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. Archived from the original on September 19, 2008. Retrieved March 26, 2007. Alt URL

- ^ Muravchik, Joshua (Nov 19, 2006). "Flop Iran". Los Angeles Times . Retrieved March 26, 2007.

- ^ Rainey, James (March 22, 2007). "Editor Resigns over Killed Stance Section". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 25, 2007. Retrieved March 26, 2007.

- ^ Martinez, Andrés (March 22, 2007). "Grazergate, an Epilogue". Los Angeles Times . Retrieved March 26, 2007.

- ^ Carroll, Rory (November vii, 2017). "Disney's blackout of LA Times triggers boycott from media outlets". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved Nov vii, 2017.

- ^ "Why I won't be reviewing 'The Concluding Jedi,' or whatever other Disney picture show, in accelerate". The Washington Post . Retrieved Nov vii, 2017.

- ^ Carroll, Rory (November 7, 2017). "Disney ends blackout of LA Times after boycott from media outlets". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- ^ "Los Angeles Times – Media Eye". Los Angeles Times. January 17, 1994. Retrieved January 12, 2009.

- ^ "The 1984 Pulitzer Prize Winner in Public Service". The Pulitzer Prizes. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

- ^ "1999 Pulitzer Prize winners for beat reporting". Columbia journalism review. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ Shaw, David (April 13, 1999). "2 Times Staffers Share Pulitzer for Trounce Reporting". Los Angeles Times . Retrieved July 30, 2012.

- ^ "The Pulitzer Prizes | Biography". Pulitzer.org. October 18, 1956. Retrieved August 16, 2010.

- ^ "2009 Pulitzer Prizes: Journalism". Reuters. April twenty, 2009. Archived from the original on April 24, 2009. Retrieved October vi, 2014.

- ^ "The Pulitzer Prizes | Citation". www.pulitzer.org . Retrieved Nov 13, 2015.

- ^ Goffard, Christopher (April eighteen, 2016). "Los Angeles Times wins Pulitzer for San Bernardino terrorist set on coverage". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 16, 2020.

- ^ "Los Angeles Times". April fifteen, 2019. Retrieved April 17, 2016.

- ^ "December 1903: Hearst's Examiner comes to L.A". Ulwaf.com. Retrieved October 21, 2012.

- ^ Cerise Ink, White Lies: The Ascent and Fall of Los Angeles Newspapers, 1920–1962 by Rob Leicester Wagner, Dragonflyer Press, 2000.

- ^ Leonard Pitt and Dale Pitt, Los Angeles: A to Z, Academy of California Press, ISBN 0-520-20274-0.

- ^ "Los Angeles Register newspaper ends publication, five months after launch". Reuters. September 23, 2014. Retrieved November eight, 2019.

- ^ "Los Angeles Register to launch as new daily newspaper". Orangish County Annals. December 13, 2013. Retrieved November 8, 2019.

- ^ "Harrison Grey Otis Southern California Historical Guild". Socalhistory.org. May 25, 2016. Archived from the original on October 2, 2015. Retrieved August 8, 2016.

- ^ "Our Annual Trade Number," Los Angeles Times, Dec eighteen, 1886, folio 4 Access to this link requires the apply of a library card.

- ^ "Our Annual Edition," Los Angeles Times, December 21, 1888, page 4 Access to this link requires the utilise of a library card.

- ^ "General Contents," Los Angeles Times, January i, 1895 Admission to this link requires the use of a library card.

- ^ Quoted in "Highest Praise Given to 'Times,'" Los Angeles Times, January 28, 1923, folio Ii-12 Access to this link requires the use of a library card.

- ^ Display advertizement, Los Angeles Times, December xiii, 1947 Access to this link requires the use of a library card.

- ^ "Bigger and Ameliorate Than Ever," page F-10 Access to this link requires the use of a library card.

- ^ "'The Country and Its Fruits' — Our Harvest Number," Los Angeles Times, September 5, 1891, folio 6 Access to this link requires the use of a library menu.

- ^ "Set Tomorrow," Los Angeles Times, September 4, 1891, page 4 Access to this link requires the use of a library menu.

- ^ The four pages of the debut March 25, 1903, effect of The Wireless were reproduced on page 11 of the March 27, 1903, Times.

- ^ "The Wireless Daily Achieved" by C. Eastward. Howell, The Independent, October fifteen, 1903, pages 2436-2440.

- ^ "Wireless Newspaper, Avalon, Santa Catalina Isle" (islapedia.com)

- ^ "Los Angeles Times website". Los Angeles Times. April 17, 2014. Archived from the original on Baronial 26, 2009. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ^ "Los Angeles Times Community Newspapers Add New Title, Increase Coverage and Apportionment with Sunday News-Press & Leader". Los Angeles Times. Jan 12, 2011.

Los Angeles Times Community Newspapers (TCN) include the Huntington Beach Independent, Daily Pilot (Costa Mesa, Newport and Irvine) and Laguna Beach Coastline Pilot. TCN newspapers maintain separate editorial and business organisation staffs from that of The Times, and focus exclusively on in-depth local coverage of their corresponding communities.

- ^ "The Pasadena Sun Publishes Terminal Effect". Editor & Publisher. July i, 2013.

- ^ "A Notation to Our Readers". April 17, 2020. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- ^ Heller, Steven. "Go West, Young Fine art Manager," Design Observer (Sept. 23, 2008).

- ^ "Los Angeles Times Festival of Books". Retrieved Oct 6, 2014.

- ^ Rebecca Buddingh (September 26, 2010). "L.A. Times off-white comes to USC". Daily Trojan. Academy of Southern California. Retrieved October 21, 2012.

- ^ "Los Angeles Times Book Prizes home page". Retrieved October half-dozen, 2014.

- ^ a b McDowell, Edwin (August 11, 1983). "Times Mirror is Selling New American Library". The New York Times . Retrieved October 3, 2015.

- ^ Korda, Michael (1999). Another life: a memoir of other people (1st ed.). New York: Random Firm. p. 103. ISBN0679456597.

- ^ "Mosby Company History". Elsevier. Retrieved Oct three, 2015.

- ^ Storch, Charles (June 27, 1986). "Times Mirror Selling Dallas Times Herald". Chicago Tribune . Retrieved June 26, 2012.

- ^ "Johnson family sells Austin TV." Broadcasting, September 4, 1972, pg. six.

- ^ "Times Mirror's deal for Newhouse's TVs gets FCC approval." Dissemination, March 31, 1980, pg. 30.

- ^ "Irresolute easily: Proposed." Dissemination, September 30, 1985, pg. 109.

- ^ "Times Mirror set to sell four TV'." Archived June 9, 2015, at WebCite Broadcasting and Cable, March 22, 1993, pg. 7.

- ^ Ember, Sydney (2018). "Union Is Formed at Los Angeles Times and Publisher Put on Exit". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January twenty, 2018.

- ^ Lachtman, Howard (Nov 7, 1976). "Fantasy Fiction by Jack London". Los Angeles Times. p. 225. Retrieved January 28, 2022.

- ^ Lachtman, Howard (Nov 29, 1981). "West View". Los Angeles Times. p. 206. Retrieved Jan 28, 2022.

- ^ 1960 Winners, The Pulitzer Prizes

Farther reading [edit]

- Ainsworth, Edward Maddin (c. 1940). History of Los Angeles Times.

- Berges, Marshall (1984). The life and Times of Los Angeles: A newspaper, a family unit, and a urban center. New York: Atheneum. ISBN0689114273.

- Gottlieb, Robert; Wolt, Irene (1977). Thinking big: the story of the Los Angeles Times, its publishers, and their influence on Southern California . New York: Putnam.

- Halberstam, David (1979). The Powers That Be . New York: Knopf. ISBN0394503813.

- Hart, Jack R. (1981). The data empire: The ascent of the Los Angeles Times and the Times Mirror Corporation. Washington, D.C.: University Press of America. ISBN0819115800.

- Merrill, John C. and Harold A. Fisher. The earth'due south great dailies: profiles of fifty newspapers (1980) pp 183–91

- Prochnau, William (Jan–February 2000). "The State of The American Newspaper: Down and Out in L.A." American Journalism Review. College Park: University of Maryland Foundation.

External links [edit]

- Official website

- Los Angeles Times Athenaeum (1881 to present)

- Los Angeles Times Photographic Annal ca. 1918–1990 (Charles Eastward. Young Research Library, UCLA-Finding Assist)

- Article for the Los Angeles Shell almost the Los Angeles Times guided tour

- Los Angeles Times at the Wayback Car (archived December 21, 1996)

- Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive (UCLA Library Digital Collections)

- Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive (UCLA Library Guide)

- Paradigm of unidentified makers of the L.A. Times "Earth", Los Angeles, 1935. Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive (Collection 1429). UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles East. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Los_Angeles_Times

0 Response to "Los Angeles Times Why We Broke Up Review"

Post a Comment